From Brand Men to Modern Product Leaders: The History of Product Management

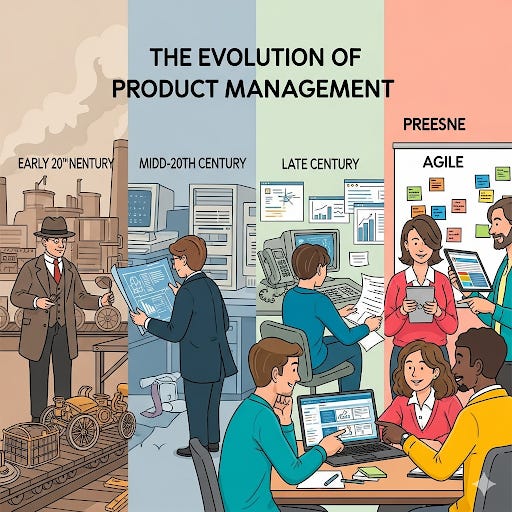

Introduction: Product management has evolved from a niche marketing experiment in the early 20th century into a critical, cross-functional leadership role in today’s tech-driven organizations. This educational overview provides a timeline of key events and shifts that shaped the product management profession. We’ll see how the first “Product Manager” jobs emerged out of business necessity, why the role became essential over time, and which companies and individuals championed its development. Along the way, we include insights and quotes from influential product leaders. (A visual timeline graphic, highlighting the milestones from 1931 to present, and pull-out quotes from pioneers like Neil McElroy or Steve Jobs, could enhance the reader’s experience.)

1930s – The Brand Man Memo: Birth of Product Management at P&G

The origin of product management is often traced to a now-famous internal memo in 1931 by Neil H. McElroy, a young advertising manager at Procter & Gamble (P&G). McElroy was frustrated that two P&G soap brands, Ivory and Camay, were competing with each other without clear ownership. In response, he wrote an 800-word memo proposing a new role he called the “Brand Man”, who would take end-to-end responsibility for a product/brand. This role went beyond advertising: McElroy insisted the Brand Man must deeply understand the customer, do market research through first-hand contact, and even experiment with packaging or promotions. Crucially, he argued that these managers should “take full responsibility” for the success of their products, relieving higher executives of day-to-day brand concerns. In McElroy’s words:

“You’ve got to start with the customer experience and work backward to the technology. You can’t start with the technology then try to figure out where to sell it.” — Steve Jobs, 1997

(Above: A potential pull quote of McElroy’s ethos or a famous product philosophy like Steve Jobs’ customer-first quote can be featured.)

This Brand Man memo became the blueprint for modern product management. P&G’s business context in the 1930s (a growing product portfolio and internal competition during the Great Depression) demanded more focused product oversight. McElroy’s idea justified hiring people to “manage [products] as independent businesses”, overseeing everything from sales figures to production and marketing strategy. Not only did P&G adopt this concept, but McElroy’s vision soon inspired others and earned him a place in history (he later became P&G’s President and even U.S. Secretary of Defense). Today, May 13 (the memo’s date) is celebrated as Product Management Day, underscoring how foundational McElroy’s “Brand Men” idea was to the field.

1940s–1950s – From Brand Management to Product Management in Industry

In the post-World War II era, as the economy boomed and consumer markets expanded, the need for product-focused managers grew across industries. Companies realized that dedicating managers to oversee a product’s life cycle—market analysis, development, and sales—was key to staying competitive in an increasingly crowded marketplace. During this time, the concept of the Brand Man broadened beyond packaged goods:

Hewlett-Packard (HP) was among the first tech companies to formalize a product manager role. In 1939, Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard founded HP, and they were actually advised by Neil McElroy in their early years. By the late 1940s, HP had created one of the first titled Product Manager positions, adapting McElroy’s brand-centric ideas to a technology context. HP’s product managers acted as customer advocates and liaisons to engineering teams. They championed a culture of solving customer problems (not just pushing products), a philosophy later known as “The HP Way”. This was a pivotal shift: it planted the seed for product management in high-tech companies, emphasizing that understanding users and working hand-in-hand with engineers leads to better products.

Consumer Goods and Automotive: Beyond tech, other sectors also embraced product management principles. Automotive giants and electronics firms in the 1950s started to institutionalize product planning and management to handle their growing product lines. For example, Toyota in Japan, while not creating “product manager” titles at the time, introduced methods that would heavily influence product management. In the 1950s, engineer Taiichi Ohno developed Toyota’s just-in-time manufacturing and Kanban visual workflow system. These innovations were about efficiency and responsiveness – reducing waste and encouraging closer communication between factory teams. The underlying principles (continuous improvement, responding to demand quickly) directly foreshadowed modern Agile practices in product development. In fact, Toyota’s lean manufacturing approach later inspired many Agile and DevOps methodologies used by product teams today.

(Visual suggestion: a timeline graphic could illustrate these early milestones – e.g. a 1931 icon for the Brand Man memo, a 1940s icon for HP’s first PM, and a 1950s icon for Toyota’s Kanban – to help readers see the chronological flow.)

1970s – Managing Complex Products: From Waterfall to Recognizing the Need for Agility

By the 1970s, industries (especially aerospace, computing, and defense) were tackling extremely complex projects. The prevailing approach to managing product development was the Waterfall model, formalized by Dr. Winston Royce in 1970. Waterfall outlined a rigid, sequential process – requirements, design, implementation, verification, maintenance – with each phase completed before the next begins. While this method brought structure and was easy to understand, it exposed a key gap in product strategy: inflexibility. Changes were hard to incorporate once a project was underway, teams tended to work in silos, and lengthy cycles meant customer feedback came too late. These flaws highlighted why dedicated product planning and adaptive management were essential. Businesses saw that focusing only on execution without iteration could “slow down innovation”. The limitations of Waterfall set the stage for new, more agile approaches that product managers would soon embrace.

During the same period, the concept of product managers continued to take root in companies as products grew more complex. A notable example is IBM, which by the 1970s had “product planners” and managers for its hardware and software lines, and Microsoft, which was founded in 1975, initially had no formal product managers. As software business grew, it became clear that engineering-driven organizations needed a role to decide what to build and ensure it truly met user needs. Early software product planning often fell to marketers or engineers wearing multiple hats, but this was about to change with the coming of more iterative methodologies.

1980s – The Tech Industry Adopts Product Management

In the 1980s, the software and personal computer revolution brought product management into tech companies in a big way. As tech firms scaled up, the product manager role became essential to bridge gaps between purely technical teams and the market:

Intuit and Customer-Centric Design (1983): One of the first software companies built on product management principles was Intuit, founded in 1983 by Scott Cook (a former P&G brand manager) and Tom Proulx. Their first product, the Quicken personal finance software, succeeded wildly because they identified a specific consumer need (managing personal finances) and built a product tailor-made for that user segment. Cook’s experience at P&G taught him to obsess over customer insights. Quicken’s success – achieved by designing for the customer and iterating based on feedback – “paved the way for more companies to begin hiring Product Managers” in tech. Intuit proved that applying classic product management (understand the user, solve their problem) works just as well for software as for soap.

Microsoft and the First Program Managers: Microsoft initially didn’t have a product management discipline – features were decided by engineers or executives. But as Microsoft’s products grew (think Microsoft Excel, Windows, etc.), even brilliant developers struggled to cover all bases. Jabe Blumenthal, a developer on the Excel team in the late 1980s, realized that the engineers were “stretched thin” just making the software function – nobody had time to talk to users, study competitors, or think holistically about usability. Microsoft created the Program Manager role (their internal term equivalent to Product Manager) to fill this gap. As former executive Steven Sinofsky explained, the new PMs acted as advocates for end users, ensuring the product’s overall coherence:“At Microsoft a new role was created in program management with the explicit goal of partnering with development… as the advocate for end users and customers.”Joel Spolsky, who was a Program Manager on the Excel team, noted that Blumenthal essentially invented the role because “none of the programmers had time to figure out how to make software that was usable or useful… there was a lot of product design work… and most programmers didn’t have the time (nor were they good at it). [Jabe] took the title ‘program manager’”. This move was hugely influential—Microsoft institutionalized product management, and the model of a technical product manager working closely with engineering became a standard in software firms.

Rise of Methodologies – Scrum’s Beginnings (1986): As tech teams sought better ways to build products, new frameworks emerged. In 1986, Hirotaka Takeuchi and Ikujiro Nonaka published “The New New Product Development Game” in Harvard Business Review, introducing the term Scrum for a rugby-like, all-hands approach to product development. They advocated small, cross-functional teams moving forward together in overlapping phases – a sharp contrast to Waterfall’s rigid stages. Their case studies (including at HP) showed that faster, more flexible product development led to superior outcomes. By the early 1990s, technologists Jeff Sutherland and Ken Schwaber had taken these ideas and formalized the Scrum framework (the first Scrum team was formed in 1993, and by 1995 they presented Scrum at a conference). Scrum gave product managers an effective way to run projects: working in “sprints”, constant feedback, and empowering teams to adapt as they learn.

1990s–2000s – Agile Revolution and the Web Boom

The late 1990s and early 2000s saw two major forces make product management even more indispensable: the Agile movement and the explosive growth of the internet/software industry.

The Agile Manifesto (2001): In February 2001, 17 software thought leaders (including Sutherland and Schwaber) met at Snowbird, Utah, and published the Agile Manifesto. This short document fundamentally reshaped product development philosophy. It declared values like “individuals and interactions over processes,” “working software over comprehensive documentation,” “customer collaboration over contract negotiation,” and “responding to change over following a plan.”. In essence, Agile called for continuous iteration, customer feedback, and flexibility – principles very much in line with the old Toyota lean ideas and with what effective product managers had been doing. Agile’s rise meant product managers shifted from long-term project planners to facilitators of rapid cycles of learning and delivery. By embracing Agile practices (like Scrum and Kanban boards), product teams could deliver value faster and adapt to change, which became crucial as web and mobile products grew more complex and user expectations rose.

Dot-Com Era and Product Management Demand: During the 1990s tech boom, companies realized they needed skilled product managers to navigate fast-paced digital markets. Web startups and tech giants alike began hiring more PMs to define online products and services. Customer experience became a differentiator, and the PM was often the person ensuring a website or app truly solved user problems. Tech industry leaders explicitly championed product management. For instance, Google, which scaled rapidly in the 2000s, made product management a core function – even requiring computer science degrees for entry-level PM roles to ensure technical acumen. Marissa Mayer, one of Google’s first product managers (and later VP of Product), so believed in the role that in 2002 she founded Google’s Associate Product Manager (APM) program. This program trained new grads in product management and produced many future leaders. Google’s success with a strong PM culture signaled to the industry that product managers were key to building great tech products.

Modern Product Thought Leaders: The 2000s also saw influential figures codifying product management knowledge. A notable example is Ben Horowitz (co-founder of Netscape and later VC) who in the late ‘90s authored a seminal guide “Good Product Manager/Bad Product Manager.” In it, Horowitz echoes McElroy’s original sentiment: “Good product managers take full responsibility and measure themselves in terms of the success of the product.” This quote underlines how owning the product outcome – the very idea from 1931 – remains the north star of the profession. Another thought leader, Marty Cagan, published Inspired: How to Create Tech Products Customers Love in 2008, which became a bible for modern product teams. Cagan and others emphasized techniques like rapid prototyping, user testing, and cross-functional teamwork, further professionalizing the field.

Lean Startup (2011): Entrepreneur Eric Ries added to this evolution with The Lean Startup in 2011. He advocated for continuous experimentation and validated learning (build-measure-learn), ideas very much aligned with product management’s focus on iterating toward product-market fit. This methodology was quickly adopted by startups and even corporate innovation teams, often led by product managers aiming to minimize wasted effort and build products that customers truly want.

By the end of the 2000s, product management was firmly established as a critical function in tech companies and beyond. Companies large and small understood that without someone orchestrating across engineering, design, marketing, and user research, products could easily fail to meet customer needs or business goals. The role had transformed from its early marketing roots into a mini-CEO of the product, responsible for strategy, execution, and user satisfaction (though the “CEO of the product” analogy is debated, the accountability implied is real).

2010s–Present – Product Managers as Strategic Leaders

In the last decade, product management has reached new heights of importance. As technology and competition accelerate, companies rely on product managers not just to launch products, but to steer product strategy that aligns with business objectives and customer expectations. Key trends and developments include:

Wider Industry Adoption: Sectors like finance, healthcare, and retail — not traditionally seen as tech — have embraced product management as they build digital products and services. Product managers are now common in banks (for mobile banking apps), in automotive (for connected car software), even in government digital services. This underscores that the PM skillset is about understanding users and delivering value, which applies anywhere.

Data-Driven Decisions: Modern product managers heavily use data analytics and A/B testing to guide decisions, something that only became feasible at scale in recent years. This has made the role more evidence-based; today’s PM is expected to balance creative vision with analytical rigor.

Education and Professionalization: The growth of the field led to more formal training. Product School, founded in 2014, was one of the first institutions dedicated to training product managers. Universities followed suit: in 2017, Carnegie Mellon University launched the first dedicated Product Management graduate degree. These developments reflect how essential the discipline has become — there’s now a recognized career path and body of knowledge for aspiring PMs.

Leadership Pathways: Many top executives have product management backgrounds, which attests to the role’s strategic nature. For example, Indra Nooyi started as a product manager in the textile industry and later became CEO of PepsiCo. In tech, Sundar Pichai (CEO of Google/Alphabet) rose through Google’s ranks after leading the Chrome browser product, and Satya Nadella (CEO of Microsoft) had a stint overseeing product units. These cases show that PMs develop a holistic view of business that equips them for senior leadership. As one industry expert put it, product managers “must be able to envisage the product from start to finish and ensure that the vision and strategy… is realized”.

Today, a great product manager is often described as a customer champion, team quarterback, and strategy owner all in one. They use tools like user story maps, KPI dashboards, and design prototypes, but their core mission remains what it was in McElroy’s time: know your customer, solve their problems, and deliver value. The contexts and methodologies have changed – from soap and print ads to AI-powered mobile apps – but the essence of the role is remarkably consistent. As product management historians like to point out, the very first principle from 1931 (“live and breathe your product and user”) still underpins the field.

Conclusion: Why Product Management Matters More Than Ever

From the humble “Brand Men” managing soap brands in the 1930s to today’s Agile product owners driving software innovation, product management has proven to be an indispensable function. It became essential because someone needed to be the voice of the customer and the champion of the product – a role neither engineering, marketing, nor sales alone could fill. Over nearly a century, visionary companies and leaders have continually reinforced this point. P&G’s McElroy taught us the value of product focus and accountability. HP’s founders showed how product managers can bridge customers and engineers. Toyota demonstrated the power of iterative improvement. Microsoft’s team highlighted that without PMs, important problems (like usability) fall through the cracks. And the Agile movement cemented that embracing change and feedback leads to better products.

As we educate the next generation of product leaders, remembering this history is not just trivia – it’s a reminder of the core principles that make product management successful. Great product managers combine the research rigor of a Brand Man and the adaptability of an Agile team leader. They stand on the shoulders of pioneers like McElroy, Packard, Ohno, Sutherland, and countless others who championed putting the product and customer at the center of business.

In the words of a modern product guru, “Good product managers take full responsibility” for their product’s success. That responsibility – to the user and to the business – is why product management will continue to be crucial in driving innovation.